Volatility smiles surfaces and option prices

Does anyone have an explanation for the currently naturally forming volatility smile and the variations in the market? This question came from our site for people interested in statistics, machine learning, data analysis, data mining, and data visualization.

Consider a more financially plausible model than Black-Scholes: Neither model is perfect, but the new one call it SVJ will be "less wrong". It is possible though not particularly easy to fit this more complicated, realistic model to the market. Big banks do it all the time. Any model, including both BS and SVJ, can be run "backwards", by which I mean that it can start with an option price and derive an implied parameter.

Toronto in May: Events & Festivals | To Do Canada

You will observe a far flatter skew for the SVJ. We see that a constant volatility parameter in the jump-diffusion is equivalent to a skew of Black-Scholes volatilities. Implied volatility has very little to do with any particular pricing model, especially not much with BS. BS is a translation tool between prices and volatility, with its own many model deficiencies. I won't get into such model assumptions because my point is an entirely different one.

My point is that IVs are entirely supply and demand driven. Whether its the IVs of an option that expires a year from now or tomorrow, whether its the IV of a 90 put equity option , 30 delta strike fx , or any other rates option, commodity option, what have you Before pretty much all IVs regardless of moneyness were priced equally.

However, the market after the stock market crash found that primarily downside protection was priced way too cheaply. Now I guess the core of the question is why: Most can be attributed to those who generally wrote such options such as sell-side trading desks but especially also floor traders who made markets in such options. They suffered steep losses and found out that they were not enough compensated for writing options such deep out of the money. It has to do with the fact that the market under-estimated the probability of such extreme events happening.

However, another important finding that causes many market makers to trade IVs far away from the money higher than at the money ones has to do with the belief that return volatility far away from current price levels tends to be a lot higher than current return volatility.

I guess the rational behind that is in a sense a paradox: I have seen on numerous occasions "inverted smirks" in equity index and stock options in that out of the money calls exhibited higher IVs than out of the money puts. But generally in this asset class space out of the money puts exhibit higher IVs than equally spaced out of the money calls. Another point that supports this general shape of the "smirk" is that empirically stock markets exhibit much higher down-side return volatility than up-side return volatility.

Panic and fear in a sense causes more irrational behavior in people than exuberance. So, in summary, all has to do with how the market prices the probability of shocks to the down and upside occurring and their severity.

On the call side this is the case because nowadays options are often utilized as leveraged bets instead of buying the underlying outright. IVs away from the money are simply more demanded than ATM ones because of the above reasons. I recommend you do not read a whole lot more into it than this because trading volatility in the end of the day is nothing else than trading any other asset, prices are set as a pure function of supply and demand, the only difference is that most underlying assets exhibit linear pay off functions where as volatility is non-linear in nature and market participants can exactly define how this non-linearity is structured by trading different strikes or option combinations.

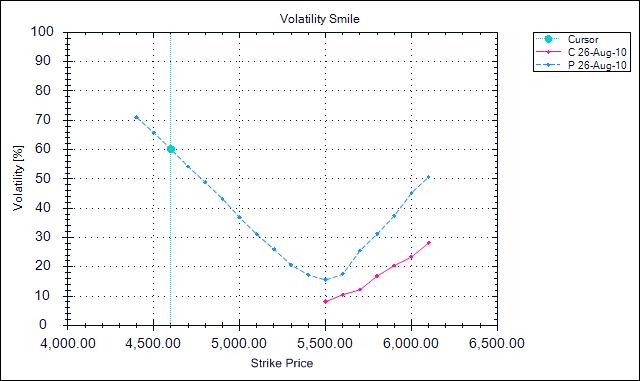

Research suggests that there is a relationship between how pronounced the smirk is and future return expectations in the underlying. The volatility smile is made out of implied volatilities. The shape of the graph a smile shows that, in the BS framework, market participants estimate different volatilities for a same asset depending on the moneyness of the option.

The Black-Scholes model is based on the assumption of lognormal returns of the underlying asset. There is much evidence and argument that stock market returns are not normal on a logarithmic basis, and there is no particular reason to assume a normal distribution, either.

In particular an implied volatility smile is evidence of "fat tails" in the returns expected by market participantsexcess kurtosis, if you will. It's been pointed out by Taleb that with over years of history, we simply don't have enough data to estimate the tails or the higher moments of the distribution of stock market returns.

That's for the last twenty years less a day of data, and does not include the crash of For a normal distribution, we would expect the kurtosis to be 3. Excess kurtosis means that a distribution has a more peaked center and fatter tails than a normal distribution, which means in the case of options a higher probability that the underlying will take on values far away from its current value come expiration time.

This is why, when excess kurtosis is not taken into account, options further from the money appear to imply a higher volatility for the underlying asset. Against the BS framework assumption, volatility is not constant and traders don't expect it to be constant. One can find hints on this issue in P. Wilmott's Frequently asked question in quantitative finance. By posting your answer, you agree to the privacy policy and terms of service.

Sign up or log in to customize your list. Stack Exchange Inbox Reputation and Badges.

Questions Tags Users Badges Unanswered. Quantitative Finance Stack Exchange is a question and answer site for finance professionals and academics.

Options Strategy Evaluation Tool: Options Analysis Software | Hoadley

Join them; it only takes a minute: Here's how it works: Anybody can ask a question Anybody can answer The best answers are voted up and rise to the top. How do you explain the volatility smile in the Black-Scholes framework? The part of this question appropriate to this site is whether the assumptions of the Black-Scholes equation lead to the solution they reach.

That question has been vetted by many and the conclusion is that the analysis is correct. Whether these assumptions are correct is not a mathematical question. After the crash people realized that extreme events were more likely than the log normal distribution suggests. They developed better option models, leading to the out of the money options to be priced more expensively to account for the greater risk.

People still talk and think in terms of BS implied vol because 1 it is convenient, 2 many other models can be considered extensions of Black-Scholes, and 3 they can use the volatility surface from the market to price exotic options. JoeCoderGuy, yes I think you make it a lot harder than it is.

Trading volatility is not that whole lot different from trading other asset classes. You seem to change your mind every single week on numerous questions you asked. Any rational behind that? I have to disagree that down-side return volatility is much higher than up-side return volatilityhistorical returns are in fact negatively skewed, but only slightly. If you look at actual data, you will find many extreme upside moves to balance the downside.

You find that realized vol was the highest when markets crashed and not when market topped out on average. This is pretty much an established fact and you can feel free to google numerous academic papers that investigated this. SRKX, absolutely disagree, and I disagreed in my comment to your answer already. Listed options prices are not a result of supply and demand of an option but supply and demand for implied volatility. If you insist IVs are the result of some formula then I highly doubt you ever worked as volatility trader.

I don't think it's only missing a variable, there are various weak points to the theory normality of returns for example.

Your question was about interpreting implied volatilities, and I'm answering that IV can't really be interpreted because they rely on a "wrong" model yielding contradictory results. I am not sure I agree with you saying "IV can't really be interpreted because they rely on a "wrong" model IV are not underlying any model at all.

IVs across the smile is how market consensus prices risk. I has nothing to do with any model in a very similar way than absolute stock prices have everything to do with market consensus and very little to do with any pricing model. Please see my answer for what I mean with that in more detail. Freddy you compute IV using the BS formula It means "what would be the volatility taken by market participants if they used the BS formula to price their option? Well that's pretty much depending on BS to me.

SRKX, sorry but I strongly disagree. Pretty much all direct market participants who manage risk on the volatility side trade volatility not options prices. The translated prices are an agreed faulty way of paying for the bought or sold volatility.

The asset that is traded and priced is volatility. I did not want to say "IV are not underlying any model at all" but wanted to say "IV are not relying on any model at all".

Volatility Smile

The double-sided exponential distribution happens to be the fattest-tailed distribution that has a moment-generating functionbut just barelyits mgf has vertical asymptotes which may impair one's ability to derive an equivalent martingale distribution of the same exponential family suitable for pricing options as in the Black-Scholes model.

JoeCoderGuy You might want to check this article out: Shalom Benaim and Peter Friz. Models with Known Moment Generating Functions. Journal of Applied Probability , Vol.

I agree with some arguments above. One can find several explanattion to volatility smile: Against the BS framework assumption, volatility is not constant and traders don't expect it to be constant This is a matter of option supply and demand volatility smile incorporates the kurtosis seen in the underlying One can find hints on this issue in P. Sign up or log in StackExchange. Sign up using Facebook.

Sign up using Email and Password. Post as a guest Name. In it, you'll get: The week's top questions and answers Important community announcements Questions that need answers. Quantitative Finance Stack Exchange works best with JavaScript enabled. Oh thank God you agree with me. Just did what you said I was curious myself the returns are quite leptokurtic, not normal.

Wilmott's Frequently asked question in quantitative finance share improve this answer. MathOverflow Mathematics Cross Validated stats Theoretical Computer Science Physics Chemistry Biology Computer Science Philosophy more 3.

Meta Stack Exchange Stack Apps Area 51 Stack Overflow Talent.